| Men play chess inside the “elderly” prisoner cell block of Henan No. 3 Prison. Image credit: Pan Xiaoling / Southern Weekly |

Decades of falling birth rates and rising life expectancy have made China one of the fastest aging countries. In 2023, its population aged 60 and above reached 297 million, or 21.1 percent of the population. While the aging population puts pressure on the already strained pension system and economic growth, elderly prisoners represent another pressing issue that requires more attention.

Unlike juvenile justice, there is a dearth of information about elderly prisoners. They don’t seem to be an area of concern prevalent or pervasive enough to warrant careful consideration. Even the Ministry of Justice acknowledged the lack of relevant statistical data and academic research, and that judicial organs and law enforcement have yet to develop sensitivity with regard to the conviction, sentencing, rehabilitation, and management of elderly offenders.

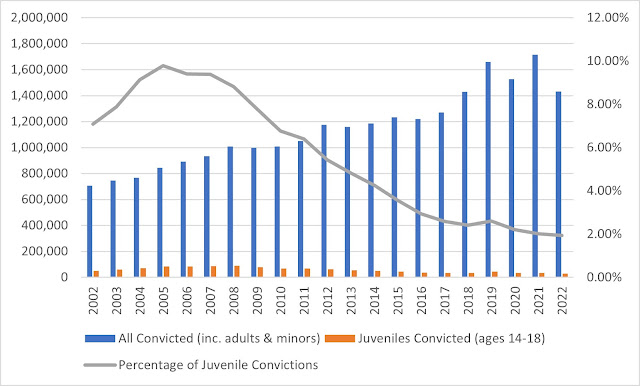

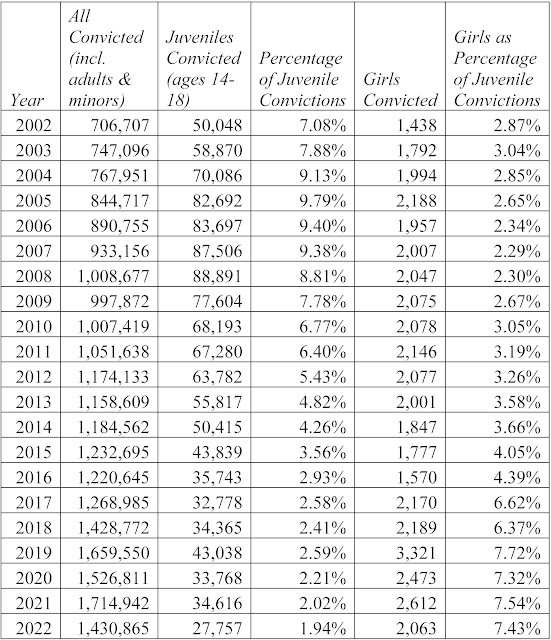

A Rising Estimate

The World Prison Brief indicated that that there were 1.69 million prisoners in China in 2017, the latest year for which statistics are available. According to Chinese sources, the number increased to two million in 2022 although it has not been officially verified. While publicly available sources have not disaggregated the prison population by age, an article published in the 2020s estimated that elderly prisoners accounted for about 5.2 percent of the prison population, and of them 65 percent were male and 35 percent were female. If we extrapolate the estimate from the prison population, an estimated 88,000-104,000 elderly people are in jail today.

Chinese legal experts generally agree that the number of elderly prisoners has been surging. First, a substantial portion have aged naturally after serving long prison sentences. Following the 2011 eighth amendment to the Criminal Law, more people who were already serving lengthy terms have had to spend more time in jail. The amendment also increased the mandatory minimum time served for life sentences before their sentences can be commuted to fixed terms. In 2015, China introduced the sentence of life without the possibility of parole for people convicted of corruption and bribery.

Elderly crime has also soared over the years. Statistics provided by the Supreme People Court indicated that the number of defendants aged 60 or above increased fourfold from 5,759 in 1998 to 23,817 in 2016 (See Table 1). However, not all of those tried and convicted ended up in jail. The 2011 Criminal Law amendment allows courts to grant offenders aged 75 or older lighter punishments, such as suspended sentences, because they are seen to pose a smaller risk to society.

|

| Source: Dui Hua, Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 |

Types of Elderly Crime

In 2012, China Court Website published its findings on this under-researched topic and summarized the types of elderly crime:

- Most crimes were committed solitarily and could be classified into two distinct categories:

- (i) crimes reflecting lower-level needs for survival or safety;

- (ii) crimes committed for obtaining economic benefits, venting negative emotions, or satisfying physiological needs;

- The crimes of bribery, abetting, deception, and harboring tended to be perpetrated by elderly people with good education, social status, and work experience attained from their careers;

- Violent crimes such as homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery were rare. Perpetrators typically had poor education and targeted vulnerable groups such as women and children as victims;

- Elderly males committed crimes such as molestation, rape, fraud, theft and harboring while women tended to commit crimes of disrupting social order;

- An increasing number of elderly people were involved in Article 300 “organizing/using a cult to undermine implementation of the law.”

Although the 2012 article did not provide relevant figures, Dui Hua’s research into court statistics released by the Supreme People’s Court showed a clear upward trend in “cult,” or unorthodox religion, cases involving elderly prisoners from 1998-2016. In 2016, the last year for which statistics are available, 523 defendants aged 60 or above were tried for Article 300, or 2.2 percent of all elderly defendants. In 1998, when Article 300 was in force for the first year, only three elderly people were tried. The number rose to 103 in 2003 when the crackdown on Falun Gong was in full swing.

|

| Source: Dui Hua, Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 |

|

| Source: Dui Hua, Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 |

|

| The Intermediate People's Court of Suzhou, Jiangsu. (Inset) Leung Shing-wan, who was 78 years old when the court convicted him. Image credit: Cantonese Group Cartography / Radio Free Asia |

|

| In January 2011, provincial authorities in Anhui grant parole or sentence reductions to 151 elderly or disabled prisoners. Image credit: Legal Daily |

- Of the 31,527 people pardoned in 2015, fifty were veterans of the War of Resistance Against Japan (World War II) and the War of Liberation (the Chinese Civil War), 1,428 were veterans of foreign wars who were not convicted of serious crimes, and 122 were over 75 years old “with serious physical difficulties” and “unable to take care of themselves.”

- In 2019, Xi announced the second special pardon to mark the 70th founding anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. This resulted in 15,858 people receiving clemency. It remains to be seen whether Xi will announce a third pardon in 2025 to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II.

.jpg) |

| On December 15, 2008, a 54-year-old female prisoner returns home after receiving parole and being released from Chengdu Women’s Prison. Her sentence was set to expire in March 2010. Image credit: Sina News |

|

| Journalist Gao Yu in the Beijing's Anzhen Hospital after her garden and office were demolished, April 5, 2016. Image credit: Su Yutong / Radio Free Asia |

|

| Wang Bingzhang, aged 77 this year, has yet to have his life sentence commuted despite repeated applications for medical parole. Image credit: Raoul Wallenberg Centre |

.png)

.jpg)